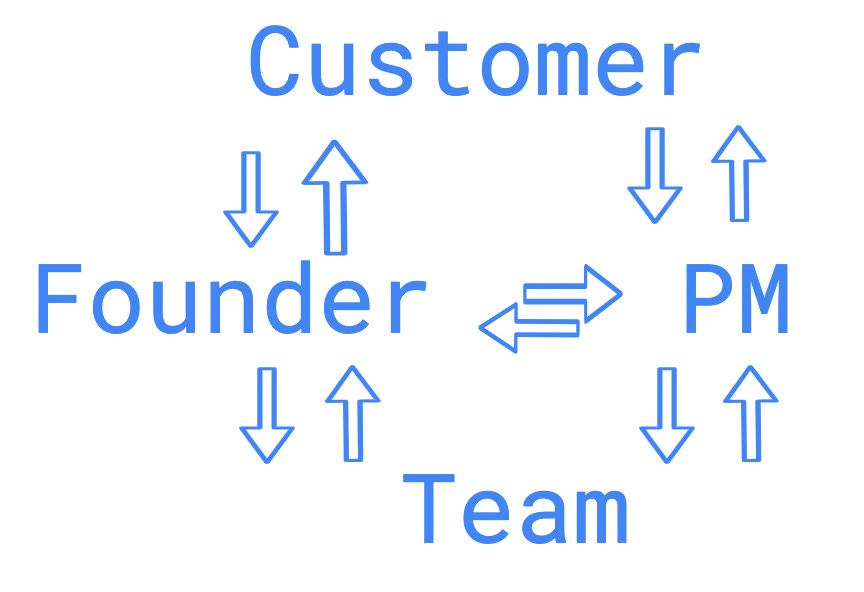

Last week I wrote about the founder as a defacto PM. This week, I'm going to cover how to make the transition to having a dedicated product person within a small organization. This is most applicable for the first product hire, but is likely to be true for the first 4-5 product hires - who will either take work from a founder, or from an existing early product hire.

Doing the job well should look easy. When this job is done well, the PM should:

🧺 Take on product work the founder was doing, as appropriate.

🕯 Illuminate how early users, customers, and data differ from the original intuition, especially as it pertains to strategy.

🤝 Keep the founder and team cohesive through a lightweight process.

There's also a few common failure modes, ranked by commonality:

🚦 The company wasn't ready for a PM.

🤥 The PM doesn't really believe in the founder.

🙅🏻♀️ The founder isn't ready for a PM.

Once again, there's no hard and fast rules about what tool to use to achieve these outcomes. When one of the "failure" modes is hit, the right answer is often parting ways.

Three ways to succeed

🧺 Take the product work founder was doing before, as appropriate.

The most precious resource the startup has is founder time. The key is to figure out how to help the founder spend their time on the work that only they can do. The first step is to find low hanging fruit: work the founder doesn't enjoy, isn't good at, is easy for an experienced PM, and will help make the team move faster. What exactly that is will vary from team to team.

A few examples:

Take a set of customer data and turn it into more clear insights (from support emails, open source issues).

Structure product discussions with a framework that helps the team get to a decision more quickly.

Make sure all the bugs someone posts in a random channel get filed, and the one that comes up twice per day gets fixed.

After a few quick wins on the low hanging fruit, the PM will have more credibility and it will be easier to take on more and more of the role. Lots of people have written about the core "tasks" of what the PM job (research, writing specs, etc) so I won't go into that further. This execution work should nearly always be taken.

The second part of helping succeed here is knowing when to stop taking product work from the founder. There will always be pieces of it that the founder can and should keep doing, which will vary founder-by-founder. The most common tension here is whether or not the product person should pick up product strategy, or if that should stay with the founder. The strategy work is often be covered by PM when the founding team has deep skills in other disciplines (sales, engineering).

🕯 Illuminate how early users, customers, and data support and differ from the original intuition, especially as it pertains to strategy.

Early companies rely heavily on vision. Even once there are early users and customers, this often becomes a set of ingrained beliefs. This type of belief will be linked to the brand - "we do it this way because we're Company!" For the founders and earliest employees this is often enough - they believed in the mission which is why they joined, and they have a deep sense of confidence in their work.

As the team grows and the company has more users, that won't feel quite as "obvious" to each additional employee or user. The early-stage PM has to tread the line between supporting that belief and surfacing evidence and data. Evidence in favor is often easy to share. It helps the founder sell to newer teammates, customers, etc. The PM can be a trusted support who helps show the why behind the belief. The team internal compass can shift from "we believe founder" to "we believe founder, and X, Y, and Z show that it's working." It might feel superfluous but it can pave the way for faster growth.

Just as important is surfacing data that conflicts with existing beliefs. In a perfect organization, this will go smoothly. In most organizations, it can feel scary or destabilizing. A good early stage PM will be able to introduce potentially controversial knowledge in a way that will be heard and rolled into the internal sense of truth.

🤝 Keep the founder and team cohesive through lightweight process.

At the beginning a company has few enough people that things can be done fairly ad-hoc. People hop on a call, Slack each other, or all sit in the same room. An early PM often joins when the company is above a "two pizza" team, and it is no longer practical to have everyone in the room all the time.

There's no golden rule for how to do this, but the early PM should have a knack for figuring out how to add just enough process that people feel grounded and included, without it feeling like a burden or bureaucracy.

Debugging the three failure modes

🚦Company isn't ready for a PM.

For the team, if you've hired product too early for the company it will feel like you're getting two sets of advice, lots of process, and no real clarity on where you're going. A key sign that this happened is a big reason the founder hired a PM because they were "too busy to do it well," but after the hire they are even busier.

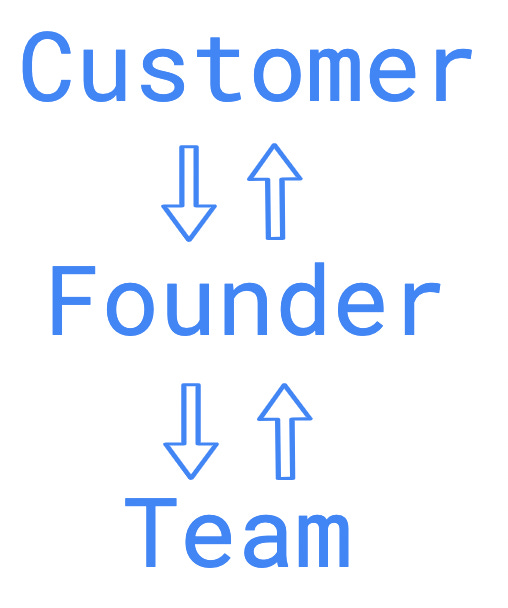

This is the most common failure mode. It very rarely makes sense to hire a PM before a company has reached some sort of product-market fit. At the end of the day there's only a few things a founder can't delegate and finding PMF is one of them. In fact, hiring product before the company is ready makes things remarkably more complicated - rather than the founder interacting with customers and the team:

there's suddenly a second person who is also interacting with customers and the team, and then going back and forth with the founder.

It's far more than twice as much communication. Often then the company will add more process to manage this communication which feels bureaucratic, and there can still be a lack of clarity on who really "owns" the product decision.

🤥 PM doesn't believe in the Founder.

The second most common failure mode is when the PM doesn't believe in the founder or becomes disillusioned with the company. This can be incredibly toxic because it often burns out the PM before they head to the next role, disrupts the whole team, and can burn out the founder. This happens a lot more often than anyone would like to admit.

More often than not, the first PM will join a system that isn't the most organized. This is fine, it's not the first thing you need to do to have a successful company. If a new PM joins and immediately starts complaining about the lack of organization, it's a red flag. They should be paying attention to see where tweaks can be made, and do that without huge fanfare or acting like they are "saving" everyone. If the PM acts like they know better about everything because this process wasn't there, this can be the first sign you're entering this potential bad path.

The crux comes in with direction and strategy. If the PM doesn't believe in the direction the founders have set for the company, they'll be pushing against it. There's an amount of healthy pushing (for instance, showing data and explanations that will illuminate new things), but there becomes a point at which the company is fighting about which way to go instead of just making decisions and going. The PM should not resent the founder being involved with product, or be quietly thinking "I could do this better." Resentment and contempt are a sign that the relationship will not work out.

One way to avoid this failure mode can be to set that expectation of the role early on. If a PM was hired to be specifically execution focused, this is less apt to happen. In the execution-focused PM case, they should make a decision of if they want to buy in to the existing strategy or not during the hiring process. The tradeoff is that this choice does tend to result in hiring less experienced product managers, most of whom want more overall impact. If an execution-focused PM can't align to the founder's strategy, they are not a good fit for the company.

If the PM was hired to be strategy focused, they need to see if there's a path to common ground. Hopefully they are senior enough to drive half of that conversation and maintain perspective. If it gap does not seem bridgeable, the role is likely to be unfulfilling for the PM, and unhelpful to the company.

🙅🏻♀️ Founder isn't ready for a PM.

PMs that aren't working out within a company (the last two patterns) will often blame the founder. That said, sometimes it is about the founder.

In one example of this, the founder might avoid hiring a PM until a point where a lot of work is falling on the floor, or when they're working harder than is possible. The team might be begging for more process or direction. Another example would be when the founder does hire a PM (often under pressure from the team or an investor). Then, even once that person is onboarded they keep diving back into the product because it's their "comfort zone."

There's not much to deliberately do here unless you're the founder. Some experienced PMs will be able to manage the founder's emotional experience of the transition and ease the pain. Sometimes the company will grow fast enough that the founder will be torn away simply because there are so many other priorities. Sometimes the founder proactively realizes and is willing to get external coaching or support. If not, this pattern often will repeat in other parts of the business, until it's forced to be addressed by the founder.

Ellen! This is awesome! I've often been on teams in a much later stage observing PMs and trying to help them, so it's cool to see the perspective of what works and doesn't work with a much smaller, earlier team.